Religious cancer sufferers are more likely to employ extreme measures to postpone an inevitable death than are the non-religious. This is the finding of a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this month. Journalistic reporting on this study has generally focused attention on the seemingly paradoxical finding that the most religious people appear to avoid “meeting their maker”. So, is the finding contradictory to what one would expect from the faithful? Let’s come back to that.

Religious cancer sufferers are more likely to employ extreme measures to postpone an inevitable death than are the non-religious. This is the finding of a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this month. Journalistic reporting on this study has generally focused attention on the seemingly paradoxical finding that the most religious people appear to avoid “meeting their maker”. So, is the finding contradictory to what one would expect from the faithful? Let’s come back to that.

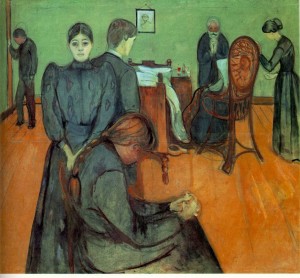

The study participants were all dying of cancer, which means they had the somewhat unique experience of knowing, at least roughly, when they would die. That must be a psychologically stressful experience for many. After all, death is a rather big transition (understatement). For the devout, death is a precursor to judgment as well. I doubt many talked much about that, but it must be on their minds. The fact is, death is a bigger deal to the devout than to the atheist whose expecting little else than lysis of the cellular membranes followed by the spilling of intracellular contents once their biologically sustaining functions have ceased, and then, nothing.

I relate to the devout, I was once a devout fundamentalist Christian. My purpose in life was the avoidance of sin, the conversion of others and the constant study of scripture. But I can also relate to the atheist because I was raised by my parents to be an atheist. I am at neither extreme now, but having spent much of my life at the extremes, I empathize with the experience of both groups and I did not find the researchers outcome to be surprising.

For an atheist, or at least for this atheist, the love of life was undermined by a deep sense of meaninglessness. I think the full scope of this is hard for many to grasp. The ultimate purposelessness of life and the universe is so weighty as to render all relative meaning and purpose as inconsequential. As a result, depression becomes a natural outcome, and even seems quite rational to the atheist. I was deeply depressed throughout my childhood. I have come to believe it was the black hole inside me, left by the absence of spirituality. It is no wonder that the atheist does not pursue drastic end of life measures.

I converted to Christianity at 19 and the pendulum swung full arc. Ultimately, despite my youth, I became an important leader in my church. As such I taught bible studies and counseled other members on a weekly basis. I came to the realization that many deeply devout practitioners had become that way, at least in part, due to an overwhelming fear of death; a fear which propelled their devotion. Others among the most devoted were reacting to a deeply painful sense of guilt and worthlessness. Such a negative self worth appears humble and righteous when expressed religiously. It is not paradoxical to imagine such people taking extraordinary measures to extend their final hours. I left my church five years later and since that time I have never fit nicely into any religious description (you might say I am post-denominational).

Ultimately, as Shakespeare once mused, death is that undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveler returns. It’s presence in our minds, whether ominous or victorious, gives weight to our lives. The finite length of a lifetime imparts an immeasurable, if earthly, value to our final moments; and perhaps an infinite value to our souls.

Reference:

JAMA

Economist

Religious cancer sufferers are more likely to employ extreme measures to postpone an inevitable death than are the non-religious. This is the finding of a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this month. Journalistic reporting on this study has generally focused attention on the seemingly paradoxical finding that the most religious people appear to avoid “meeting their maker”. So, is the finding contradictory to what one would expect from the faithful? Let’s come back to that.

Religious cancer sufferers are more likely to employ extreme measures to postpone an inevitable death than are the non-religious. This is the finding of a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association this month. Journalistic reporting on this study has generally focused attention on the seemingly paradoxical finding that the most religious people appear to avoid “meeting their maker”. So, is the finding contradictory to what one would expect from the faithful? Let’s come back to that. For money you can have

For money you can have “Brevity is the soul of wit” according to the great bard, William Shakespeare. The same applies to the social networking fad, Twitter.

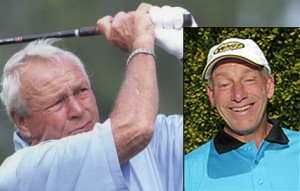

“Brevity is the soul of wit” according to the great bard, William Shakespeare. The same applies to the social networking fad, Twitter. Tom Sullivan (famous blind musician) met Arnold Palmer (famous golf legend) and said “Arnold, I can beat you at golf, I know I can, it doesn’t matter that I am blind, I will bet you $1000 that I can beat you.”

Tom Sullivan (famous blind musician) met Arnold Palmer (famous golf legend) and said “Arnold, I can beat you at golf, I know I can, it doesn’t matter that I am blind, I will bet you $1000 that I can beat you.”

How to fix it, how to avoid it.

How to fix it, how to avoid it.